Photographer Peter Steinhauer travels to almost every region of Vietnam, returning many times to take photograph of the country (Photo courtesy of Peter Steinhauer) Photographer Peter Steinhauer travels to almost every region of Vietnam, returning many times to take photograph of the country (Photo courtesy of Peter Steinhauer) |

“I was determined to do this work and to do my project in my humble way also to help the Americans to understand what Vietnam looks like and what the people look like and also to help Vietnamese, Americans to understand where they are from and try to help people heal through my photography. That would be worth it for me,” Peter Steinhauer said.

In his recent exhibition “Vietnam - A 30 Year Retrospective” in Hanoi, Peter showcased 60 large-format photographs representing some of his most outstanding artistic achievements, reflecting his exceptional technical mastery, while portraying Vietnam’s diversity and richness, from natural landscapes to scenes of everyday life.

For many Americans, even decades after the war, Vietnam is still viewed through the shadow of conflict. Peter Steinhauer’s work moves beyond that perspective. Through light, form, and deep respect for his subjects, he creates a new visual language, the one that celebrates the beauty, dignity, and humanity of Vietnam.

Through his art, Steinhauer nurtures understanding and healing.

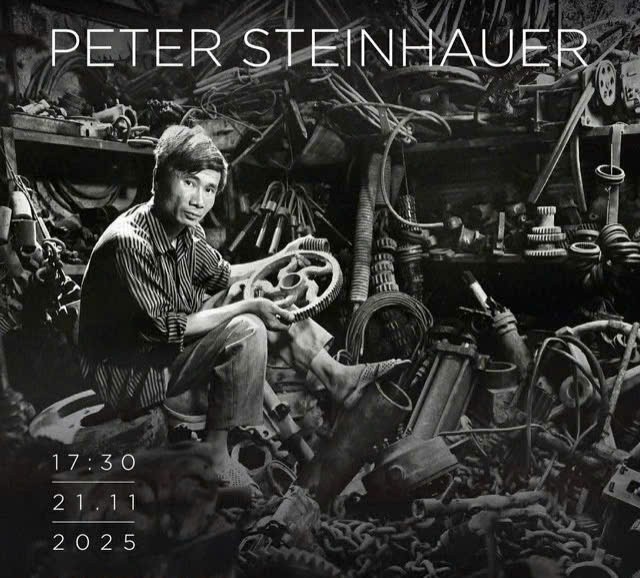

A highlight of the exhibition is a series of monumental black-and-white photographs depicting an ironworker in a small workshop on De La Thanh Street and an elderly herbalist. These were among the very first images Peter captured when he arrived in Vietnam in 1994. Through these portraits of ordinary Vietnamese people, Peter recorded his earliest impressions of the country. In particular, the photograph of the herbalist in Hanoi’s Old Quarter remains one of his most striking and memorable early works.

Peter says he is most impressed with the photo taken during his first visit to Hanoi in 1993, capturing an elderly man named Le Van Khoi. (Photo courtesy of Peter Steinhauer) Peter says he is most impressed with the photo taken during his first visit to Hanoi in 1993, capturing an elderly man named Le Van Khoi. (Photo courtesy of Peter Steinhauer) |

Peter said: “This was actually in 1993. This is one of the first portraits that I made for my photo book and his name is Le Van Khoi. He was an herbalist. He was just actually right in the front of Hoan Kiem and if anyone knows café Dinh or café Trung, it was just on the ground level, just right below the café and I saw him sitting there with a small little desk lamp that was lighting up his book. And for me, I'd never seen a person like this before with his long white beard, his hair, but you could tell he was very educated and reading, always just reading these very large books.”

Peter’s first connection to Vietnam came from the photographs his father brought home. His father was a maxillofacial surgeon who served in Da Nang during the war from 1966 to 1967, treating injured American soldiers as well as wounded prisoners. Alongside his medical work, Peter’s father developed a deep affection for photography. Whenever he could, Peter’s father photographed the world beyond the military base, peaceful countryside scenes, village life, children, and elderly people. These images revealed a very different side of Vietnam which is humane, calm, and resilient, far removed from fierce battles surrounding it.

Peter grew up immersed in these photographs and the stories behind them. Those early images stayed with him, awakening a deep curiosity about the country and developing a connection with Vietnam.

“My father was involved in the health. Mine is through art and culture. Those two things don't always mesh, but I feel very strongly about people heal through, you know, if you can't communicate with another culture, people communicate with each other through art, through music, through light. And that is what my work is. I'm a visual artist. And so, in a very modest way, from when I came here, growing up with Vietnam in my life, I can see images of the war. And I, from a very young age, I always wanted to see inside people's houses. I wanted to see about the life here. I didn't want to see about the war, because I saw those through all my father's photographs. And so, I had a rule when I moved to Hanoi that I would never photograph anything about the war. I would focus on this country as a 3,000, 3,500-year-old country, culture,” said Peter.

Nurturing a long-held dream, Peter came to Vietnam in 1994 after graduating from art school in Colorado. From the moment he arrived, he felt an immediate sense of closeness to the country, Vietnam quickly became more than a destination it was a place he came to consider his second home.

Peter later lived in Hanoi for four years from 1993 to 1997 and in Ho Chi Minh City for eight years from 1998–2006, while continuing to return regularly over the past three decades. Throughout these years, he has captured thousands of photographs during his passionate and inspiring journeys across Vietnam.

The photo of a hanging bridge in Son La province taken by Peter Steinhauer in 1995. The photo of a hanging bridge in Son La province taken by Peter Steinhauer in 1995. |

Peter photographs range from aging apartment blocks in Hanoi, the narrow alleys and small streets of the capital’s Old Quarter to bustling markets from north to south, natural sceneries like Ha Long Bay, the Mekong River Delta, a suspension bridge crossing a river, Van Cao- the composer of Marching Song - Vietnam’s national anthem, a smiling mechanic with his sleeve darkened with sweat.

For Peter, photography is more than capturing a fleeting moment, it is a long-term process of witnessing and recording change. Each return to Vietnam becomes a journey back to the places he once photographed, allowing him to see whether those scenes remain as he remembered them or have quietly transformed over time.

Peter said: “This is Nguyen Thai Hoc street now. I could go down Nguyen Thai Hoc and there's, you know, you can go down Nguyen Thai Hoc all the way to Thanh Xuan in like five, six minutes. There were no cars. Nguyen Thai Hoc now is one-way street, but it was back then two-way street. And here, you know, in this photograph, I call it Nguyen Thai Hoc flowers. This is where you could go there and they always had people selling flowers on the side of on the side of the road. You can see the French house in the background. But, you cannot see this whole house because it's covered with a big billboard, you know, advertising for something.”

He added: “This is the bird market at Cho Hang Da. This was in 1998 and so this was just on the outside of Cho Hang Da and you know it doesn't and Cho Hang Da itself was completely different than what it is now. It was a real market inside. But now it's, you know, it's almost like a mini shopping center inside. But back then it was completely different.”

The water tanks on Nguyen Cong Tru street. The water tanks on Nguyen Cong Tru street. |

At first, Peter’s photos were mainly focused on portraits and landscapes, but over time he became increasingly drawn to the theme of urban life. He had a special interest in capturing changes in Hanoi, which can be seen in Peter’s project of Nha Tap The - the old living quarters.

Peter said those old buildings is a vital part of Hanoi’s history which was once modern, community-centered housing that has aged and transformed over decades. As these Soviet-era blocks face demolition amid rapid urban change, he photographs them to preserve a way of life and architectural legacy that may soon disappear.

“So the water tanks and the Nha Tap The project I photographed that I went to every region in Hanoi and photographed them. Very graphic images. I showed what they were like and the the water tanks the one you were re referring to is on Nguyen Cong Tru street and that is where that image was made. I knew Hanoi would change and so my job and my focus is to photograph it in this style to preserve it at what I feel this at its best time” said Peter.

Another thing of Vietnam that really attracts Peter is the community life and social interaction at Vietnamese market places. Markets are really the places for you to understand much about life and culture of the local people. This is demonstrated in Peter’s photo collections of markets as he has travelled to markets of Asian countries, including Vietnam. Peter said for centuries, markets have been a focal point for people of villages and in cities to go for food and trade, but almost equally as important, they are a place of gathering for socializing. Each image is accompanied with high definition audio of what is taking place in that scene in the language of that area.

He said: “It's a place of community. It's a sense of community and people go there to meet to have food, coffee or you know to eat you know whatever any type of food and or actually and they use it of course to buy goods. Even though Ben Thanh Market right now is very touristy, it's still a central market but they are being replaced with supermarkets. There's refrigeration the you know and all of that and so those markets are being torn down also. What I am trying to do is preserve those and not just photographically but I go in and I record the sound. What the beautiful thing about Vietnam is all the different accents in the different regions.”

A cathedral in Ninh Binh province (Photo courtesy of Peter Steinhauer) A cathedral in Ninh Binh province (Photo courtesy of Peter Steinhauer) |

Peter’s most recent photo project focuses on the cathedrals in Ninh Binh province, capturing the grandeur of French-era church architecture as it blends seamlessly with Vietnamese culture. These works are featured in his photo book SPIRES: Cathedrals of the Red River Delta, which documents these remarkable structures as both architectural landmarks and living cultural spaces.

“So I am a Christian. I'm not a Catholic, but I photographed this for a reason, not any religious reason at all. The main reason was I'm an architectural and structure photographer and these cathedrals as you know they're I focused only on the Red River Delta which is Nam Dinh, Thai Binh, Ninh Binh province, south of Hanoi 100 150 kilometers and I focused only there because that's where Catholicism came into Vietnam in the year 1533. So that is why I focused only in that region because there's Catholic cathedrals everywhere in Vietnam, but that would take me years and years and years and years to go through,” he said.

Peter’s photographs have won over audiences not only through his technical mastery, but also through the time he spends observing, feeling, and quietly documenting what he sees. Most of the works on display are in black and white, a choice that, as Peter explains, creates a strong sense of authenticity and intimacy, bringing out the raw, natural beauty of people. At the same time, his black-and-white landscapes carry a timeless quality, making the scenery feel enduring and almost unchanged by time.

“I was very interested in black and white photography. As an artist, I feel you can express yourself through black and white very well. You can create... We don't see in black and white, so we can create a world through our photographs that we don't always see, and it can transport people into a different dimension. When you're seeing black and white, you can make them look like a different world, in a sense. And that drew me to black and white as a young artist. Photography focuses on details and context,” he said.

The black and white photos evoked special emotions and made strong impressions on the viewers. American musician and video producer Hal McMillen said he was impressed by the photos of ordinary Vietnamese people, especially people in the mountain areas, all in black and white.

“Yeah. I like it. There's something about black and white that stirs a different emotion for me. You're not distracted by the color. You're more pulled into the image and not like, oh there's a pretty red or a pretty blue or that. It's like, hmm, what's really going on here? I think it draws me in deeper to the photograph, actually,” said Hal McMillen.

The photograph featuring a mechanical shop owner on De La Thanh Street is one of the photos Peter Steinhauer captured when he first came to Vietnam (Photo taken at the exhibition) The photograph featuring a mechanical shop owner on De La Thanh Street is one of the photos Peter Steinhauer captured when he first came to Vietnam (Photo taken at the exhibition) |

Duong Thu Hang from Hanoi Studio Gallery, which is hosting Peter’s photo collection, shared that viewing his photographs filled her with a deep sense of nostalgia.

“I first heard Peter’s name decades ago when he exhibited his work in Hanoi. I’ve always admired photographers who came to Vietnam in the early 1990s and spent decades documenting not just beauty, but everyday life that has since become part of our cultural heritage. His photos are deeply moving. They show who we were and how Hanoi has changed. I’m especially struck by his portrait of a mechanic in a small recycling workshop on De La Thanh Street, which feels like it emerged from a long post-war period. Peter also captured other powerful images of Hanoi, especially those reflecting change. He photographed overpasses 20 years ago, and then returned years later to photograph the exact same spots again.”

Erin Phuong, Peter’s Vietnamese-born wife, left her homeland at a very young age and grew up with almost no connection to Vietnam. That connection only resurfaced when she unexpectedly encountered one of Peter’s photographs of Vietnam at an exhibition in Washington, D.C. In that moment, memories of her mother and a deep sense of her Vietnamese roots suddenly came flooding back.

Erin Phuong (in the middle) Erin Phuong (in the middle) |

Erin Phuong said: “During the war, Peter’s father was a doctor who shared many stories about Vietnam, and after the war he even founded a program to support Vietnamese doctors in the US. That’s how Peter’s love for Vietnam grew, and when he later came to photograph the country, he felt an immediate sense of belonging that only deepened with time. I left Vietnam very young and had little connection to my roots until I visited an exhibition in Washington, D.C. and saw Peter’s photo of a bamboo bridge. It suddenly awakened childhood memories and thoughts of my mother. I sought out the photographer, met Peter, and through his stories and images, I unexpectedly found my way back to my homeland and my roots.”

Driven by that shared love, they co-founded the Vietnam Society, an independent, non-governmental organization dedicated to promoting Vietnamese contemporary culture and art. Since 2022, the organization has hosted the annual Vietnam Week in Washington, D.C., featuring film screenings, fashion shows, cuisine, music performances, and literary talks, with the support of leading US institutions such as the Smithsonian museums, the Kennedy Center, and other major organizations. They see it as a “window” through which overseas Vietnamese, especially younger generations, can continue to reconnect with their roots and gain a positive, contemporary perspective on Vietnam.